China’s Newest Examination Guidelines: Novelty and Inventive Step for Compounds (Part II)

April 2021

This is Part II of a three-part series summarizing the Examination Guidelines that were released by the CNIPA on January 15, 2021. Part I of this series covers examples on post-filing supplemental data. Part II covers examples on novelty and inventive step for chemical /compounds inventions. Part III covers examples on inventive step for biological inventions.

The new Examination Guidelines have clarified the burden of proof that an examiner has to make a case for novelty, especially in cases where it’s not black and white. More specifically, the Guidelines have removed a previous example of novelty-destroying prior art and replaced it with a new, more nuanced one.

The old example said that prior art is novelty destroying even if it does not recite compound if it provides a method for making the compound that is similar/identical to the method of the claimed compound. The old example was rigid and made a lot of assumptions regarding whether teaching a method of making something necessarily taught that the product was also made.

The new Examination Guidelines change the standard and incorporates what one of skill in the art would have thought. Below is the new standard:

Compared to a claimed compound, if a prior art document discloses

- a chemical name, molecular formula, or other structural information to make one of skill in the art consider that the claimed compound has been disclosed

- Insufficient structural information but in combination with other information in the document (e.g., physical & chemical parameters), one of skill in the art would consider is substantially the same as the claimed compound

The claimed compound is not novel, and the applicant has the burden of proof to show otherwise.

This new version takes into account what one of skill in the art would consider to be substantially the same, and also requires at least some structural information demonstrating to one of skill in the art that the compound has been disclosed (even if it is not complete).

It’s quite evident from these changes that examination in China is become more nuanced and less rigid, with a focus on whether one of skill in the art would consider something to be disclosed or not.

Inventive Step: Problem Solution Approach

The new Examination Guidelines have tightened the analysis that examiner must make when making an inventive step determination. Previous according to the old guidelines, examiners would first analyze whether a claimed compound was structurally close to the closest prior art compound. If the examiner decided they were close, then the applicant would need to provide unexpected results in order to overcome inventive step. This approach gave the examiner quite a bit of latitude to determine whether two compounds were structurally close, and resulted in examiners often rejecting claims based on hindsight.

These Guidelines are much more objective and rigorous in their approach. After determining the structural differences between the closest prior art compound and the claimed compound, Examiners must then a) determine the technical problem solved by the effects of the structural differences in the claimed compound and b) determine whether the existing technology as a whole provides motivation to solve the problem through structural modification.

Now, unlike in the past where an Examiner could just (based on hindsight) determine that two structures were “similar”, the Examiner has the burden to show how the existing technology provides motivation for the change.

In some ways, the standard for inventive is starting to look a more like Europe’s or the US’s approaches to obviousness, which are based on the standard of whether a skill person in the art would find an invention obvious or have motivation to change based on the prior art and the problem to be solved.

We should note however, the level of a skilled person in the art in China is not the same as a person having ordinary skill in the art in the US. Accordingly to the Guideline, a “skilled person in the art” in China is an all-knowing expert, simultaneously possessing all prior art knowledge publicly available at a particular time. He or she is by no means ordinary.

As a result, Examiner freely combine two pieces of prior art to reject a claim on the basis of inventive step, even if there is no explicit teaching or motivation to combine. As long a combination can be reasonably done, the Examiner will consider that this “all knowing” skilled person would have the requisite motivation.

Despite some of these real world concerns, the new Guidelines are still a welcomed change that move towards leveling the playing field and (hopefully) compelling examiners to be more objective and precise in how they issue inventive step rejections. Examiners still have quite a bit of leeway in discerning what would “motivate” a skilled person based on the existing technology as a whole. Only time will tell how these Guidelines will change the actual practice at the CNIPA.

Compounds

The Examination Guidelines further provide several examples that help examiners consider whether two structures would be similar or not.

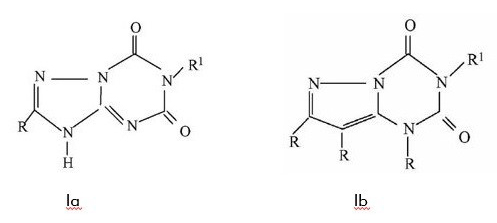

Example 1: Different Structure: Same or Different Activity?

Example 1 shows two chemical 5-6 fused ring structures differing only by one atom in the ring (nitrogen versus carbon). Due to the unpredictable nature of the chemical arts, the Guidelines considers these two structures to be different. Accordingly, without any teaching that Ia can be converted to Ib and still keep its activity, Ib would be considered inventive in view of Ia, even if they had the same activity. This example is helpful in confirming that the Examination Guidelines consider different core structures (even by just one atom) are not considered “close”, and thus there is no expectation that they should have the same properties.

Example 2: Different Indication, Different Structure

In Example 2, two similar looking compounds differing only by the terminal group at the end of a sulfonamide, are shown to have different uses. IIa is effective as an antibiotic, while IIb is useful as an anti-diabetic. The Guidelines also considers that there is no motivation for one of skill in the art to change IIa to IIb in order to achieve the anti-diabetic effects of IIb. Accordingly, IIb is inventive in view of IIa, regardless of what activity it has.

In this example, the key point is that the two compounds are useful in two different diseases. This alone makes IIb inventive and not predictable based on IIa’s structure, even though it is arguably a bit close.

Example 3: Isosteres, Same Indication, Same Activity

Example 3 is interesting in that it gives a example of two compounds which only differ by one functional group (NH2 and CH3, which are considered classic univalent isosteres). In this case, because one of skill in the art would think that they are interchangeable, two compounds that differ only by a known isostere (and have the same efficacy in the same disease area), will not be considered inventive.

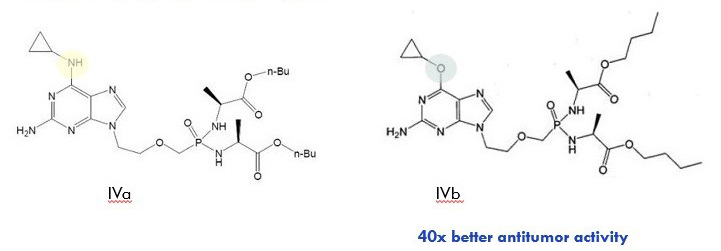

Example 4: Isosteres but with Surprising Activity

In Example 4, two molecules that only differ by one atom (nitrogen versus oxygen) are considered similar because -NH- and -O- are considered univalent isosteres. However, surprising activity of the claimed compound (40x better anti-tumor activity) is unexpected and therefore makes compound IVb inventive over prior art compound IVa.

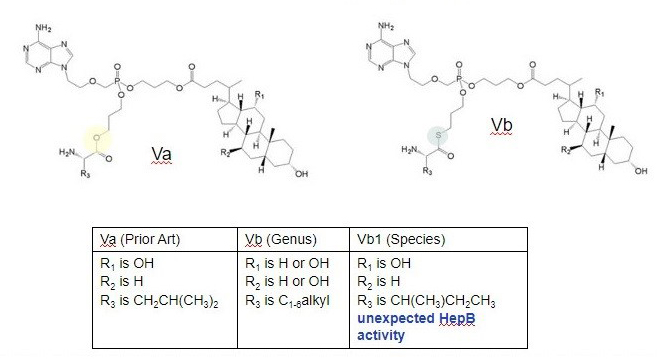

Example 5: Genus vs. Species, Isosteres, Surprising Activity

Example 5 highlights what happens when a claimed genus differs by a prior art species only by an isostere. In this example, prior art compound Va would fall within the scope of the genus of Formula Vb, except for the replacement of a sulfur for an oxygen atom. According to the Guidelines, based on structure alone Vb is not inventive in view of Va.

However, if a species within Vb, such as Vb1 shown above, has unexpected properties, then species Vb1 is inventive over the prior art.

In Part III of this Series, we will discuss the remaining examples on inventive step for biological inventions and also our general thoughts on these new Examination Guidelines.

We will keep you updated on any further developments. Stay tuned for more important updates on IP law in China.

Please contact us with any questions: eip@eipgroup.asia.

Eagle IP are experts in patent law and we offer a one-stop service for your global IP needs.

This article is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered legal advice or a legal opinion on a specific set of facts.